Cows are phenomenal biological processing plants on four hooves. When a cow eats grass, it removes the carbon chains from the plant and microorganisms in the rumen, a drum-like stomach, produce microbial protein, which the cow then digests. Cows have four stomachs in all, but the rumen is the largest. It’s where food goes after traveling from the cow’s mouth through its esophagus. It’s also why cows are known as ruminants, a category of mammals that includes goats, sheep, deer, moose, bison, and buffalo.

Inside a cow’s rumen, millions of microorganisms begin the digestion process. Later, when these microorganisms die and drift down through the digestive tract, they’re absorbed in the cow’s intestine. But there’s a lot more that happens along the way. During digestion, the microorganisms and the digestive process release methane and heat. This gas collects into big bubbles and is released from the cow through eructation (burping) or flatulence (farting). The size of these bubbles is important, and it takes the right type of diet to create the right kind of bubbles.

Maybe the best way to make this point is to explain what happens when a cow eats nightshade, a type of flowering plant. Cows will eat most anything, including the leaves and branches on bushes and trees. But when a cow eats nightshade, the surface tension in the rumen changes. Gas doesn’t collect normally and the bubbles stay small. In turn, this causes the cow to bloat. Bloating increases the internal pressure on the cow’s organs. If there’s too much pressure on the cow’s heart and diaphragm, the animal can die.

Fortunately, farmers and ranchers can correct this condition by putting mineral oil in a soda bottle, opening the cow’s mouth, and pouring in the liquid. It’s important to hold down the cow’s head a bit so that the liquid goes into the stomach and not into the lungs, and to stand back to avoid getting splattered by digestive material. The mineral oil works by changing the surface tension in the cow’s stomach so that bubbles of the right size form normally. The microorganisms in the rumen and the digestive process again produce methane, and the cow releases gas through eructation and flatulence.

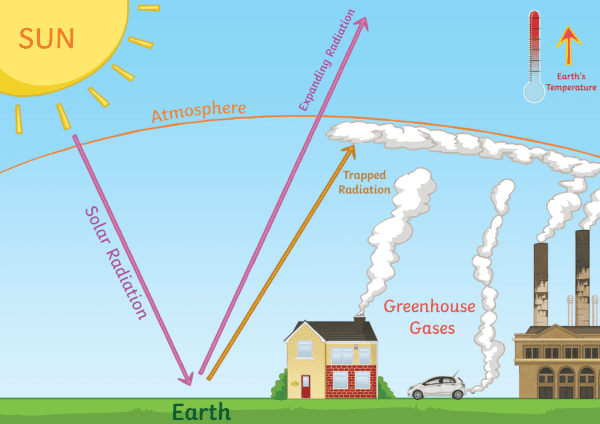

Over the last few years, cows have been blamed for contributing to climate change. In fact, the entire beef industry has been criticized. Is this fair? Yes, it’s true that methane is a greenhouse gas, though it’s not the primary one. Critics of the beef industry may then argue that methane is ten times more potent than carbon dioxide (CO2), which comes from the burning of fossils fuels. But there’s a lot more to the story.

Let’s look at cows, carbon, and the environment from a different perspective. The carbon chains that cows remove from grass have been part of our natural environment for millions of years. They weren’t just released from the tailpipe of a car that has an internal combustion engine. Cars aren’t a new invention, of course, but neither are they part of a naturally occurring cycle – and they certainly haven’t been around for millions of years.

Ruminants have been around before automobiles. Long before the first Europeans arrived, the bison roamed the North American Great Plains. There are fewer of these free-ranging ruminants roaming about these days, but their numbers were prolific. Now here’s something that hasn’t changed. Grass takes carbon out of the atmosphere in the photosynthesis process and releases oxygen. It’s the same process that’s been going on for millions of years.

Here at Go Natural Education, we encourage you to think critically about claims that “cows are bad for the environment.” For starters, they’re not outside of the environment; they’re an important part of it. The digestive cycle of cows and other ruminants has gone on for millions of years, and a cow that walks on grass is good for the land because its hooves break up and aerate the root system.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this article and encourage you to subscribe to our YouTube channel.