In our last article, we learned how young beef cattle are shipped to a feedlot where they are fed primarily a grain diet. This enables the cows to gain a significant amount of weight. It also promotes marbling, the white flecks and streaks of intramuscular fat that create a marble-like pattern. During cooking, marbling helps to keep the meat moist while adding flavor. Some cooks also add butter, and some recipes may call for herbs such as parsley.

From Feedlot to Processor

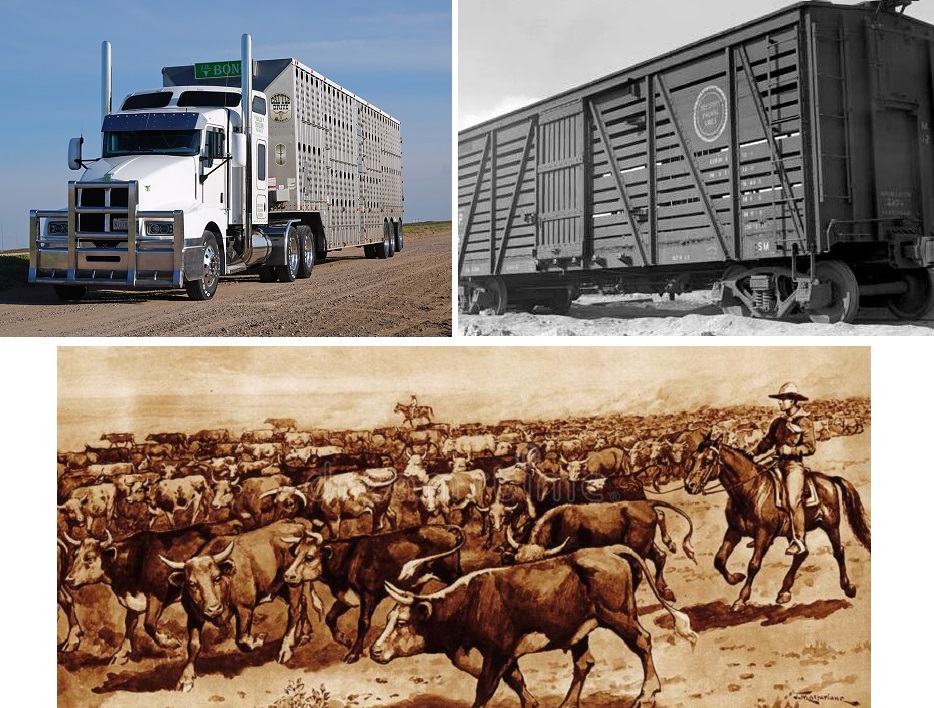

Months before a steak reaches your table, feedlot cattle that are ready for harvesting are shipped to a meat processing facility. Typically, the animals are transported in large cattle trailers that are pulled by a tractor, a type of truck that is designed to pull heavy loads. These are the same tractors that are used in the tractor trailers, or semis, you see on the highway regularly. The size of a cattle trailer can vary, but some are double-deckers that can hold 40 to 50 steers, young neutered male cattle that are raised for beef.

Prior to the development of tractors and paved roads, steers were often transported by rail in stock cars instead. This type of rolling stock resembles a box car but has louvered sides instead of solid ones for ventilation. Prior to the arrival of railroads in the West, the great Texas cattle drives that began in the 1860s also moved cattle, often north to Kansas. The cowboys who worked these cattle drives had to overcome many hardships, and transportation by cattle trailer is much easier.

The Cost (and Value) of Hanging Around

Today, Texas still conjures up images of cowboys – and Kansas is still home to many feedlots and processing facilities. For example, cattle trailers regularly bring steers from a feedlot in Dodge City to a processing facility in Garden City. When the trailers arrive, the cattle are unloaded, passed through a chute, and slaughtered. Meat processing at a facility like this is highly efficient because, just as in manufacturing or other industries, time is money.

Space within a facility also comes with a cost. That’s why large processors don’t hang the meat from hundreds or thousands of cattle on-site to let the meat age. Instead, they cut the meat into sides or quarters that are loaded onto refrigerated trailers, which are also pulled by tractors. Typically, the meat is hung by hooks from the trailer’s ceiling. It may be sent to a refrigerated facility for hanging and to age, but the meat is ultimately sent to restaurants and supermarkets.

Hanging is a culinary process that improves the flavor of beef by allowing the meat’s natural enzymes to break down the tissue, which contributes to tenderness. Dry aging, as it’s known, allows the water in the meat to evaporate, which concentrates the flavor. Typically, the sides or quarters that a processor cuts are hung under carefully controlled conditions of temperature and humidity. Large processing facilities may store hundreds or thousands of sides of beef.

Inspections and Grading

In the United States, facilities like the one pictured above need to meet U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) standards for hygiene. They also need to be federally inspected. As the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (NCAR) explains, the inspection and grading of meat are two separate USDA programs. Inspection is mandatory and taxpayer-funded, but grading for quality is voluntary and paid for by the meat processor. This is an important distinction, but both have implications for the processor.

For years, there have been concerns that the USDA does not have enough meat inspectors. The average annual salary for these federal employees is about $66,634 and the workload is significant. For meat processors, these staffing shortages have reportedly resulted in missed or inadequate inspections. Failing to comply with USDA regulations comes with the prospect of fines or prison time, however, as this Amish producer of organic milk has learned.

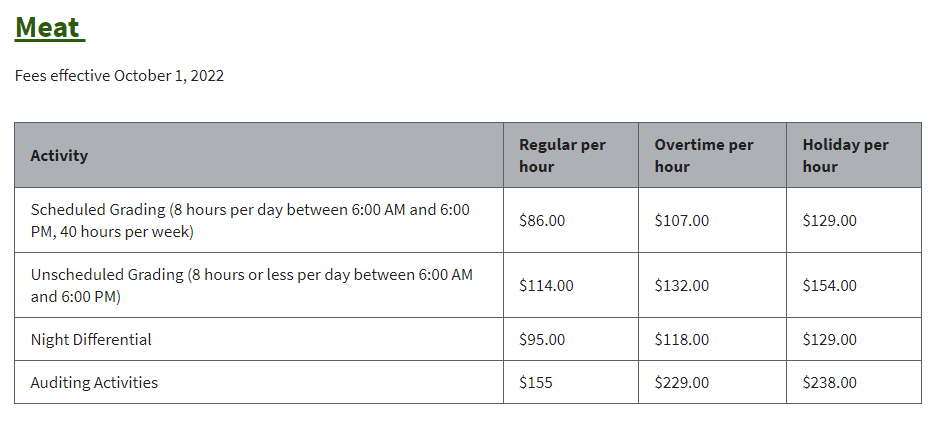

If a meat processor wants the USDA to grade the quality of its products, then the processor must pay the federal agency according to this fee schedule in the table below. For a small local processor, these fees can represent significant expenses.

Note: In the U.S., facilities that produce meat products sold entirely within a state can be inspected by a State Meat and Poultry (MPI) program instead of by the USDA. However, state MPI programs must enforce requirements at least equal to those imposed under federal legislation. The USDA publishes a list of states with and without MPI programs. Florida, where Go Natural is located, is among 31 states that do not have MPI programs.

From Market to Table

At the supermarket, meat is usually put into polystyrene trays with an absorbent pad and then wrapped in clear plastic. The average consumer looks for meat that is red and wet, but dry aged beef doesn’t look like that – and many people say it tastes better. Plus, if you buy meat at the supermarket, you probably don’t know much about where it comes from. As we explained in our Five Reasons Local Meat is Better Series, however, knowing the source is just one of the benefits of buying meat locally.