Dr. Alan Franzluebbers is a Research Ecologist with the USDA Agricultural Research Station on the campus of North Carolina State University in Raleigh, North Carolina. Recently, Dr. Franzluebbers presented the third webinar in an 11-part series called Grazing Land Management and Soil Carbon. The topic of his talk was “Can soil organic matter really be changed on grazing lands in North Carolina?”

The Role of Climate

Dr. Franzluebbers began his lecture by stating that 25% of the land in the Southeastern U.S. consists of crop land or pastureland. Soils there have lower levels of carbon because the region’s warm, humid conditions cause organic matter to decompose more quickly. Yet there’s also a higher potential for the accumulation of biomass because of the region’s longer growing season.

The difference between biomass production and decomposition, Dr. Franzluebbers explained, is what determines soil carbon levels. In other words, a warm-weather region can have a high potential for biomass production but low levels of soil carbon because organic matter decomposes faster than new biomass can accumulate.

The Role of Region

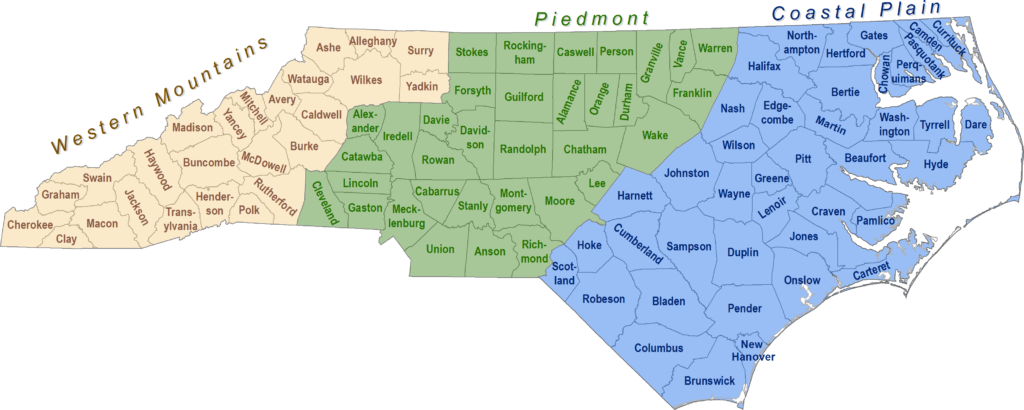

In North Carolina, there are visible differences between the state’s coastal, piedmont, and mountainous regions. Yet this doesn’t determine soil carbon levels either. Rather, “land use has a really strong effect independent of the physiographic region”, Dr. Franzluebbers explained. Physiography, the study of Earth’s landforms, categorizes features such as beaches, foothills, and mountains based on the forces that shaped them.

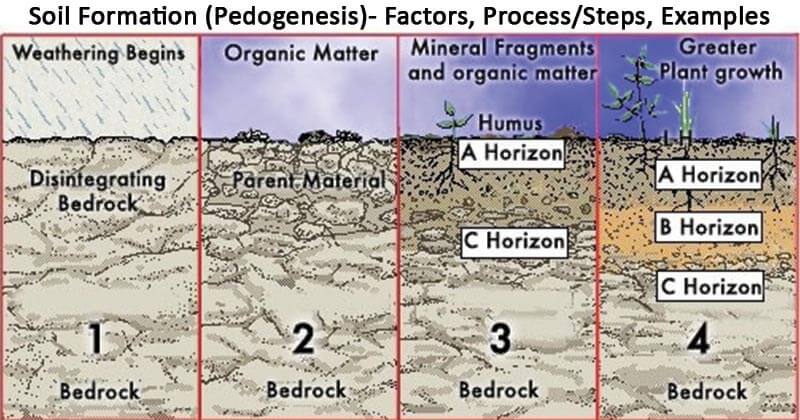

A place like Nebraska is flatter than North Carolina, but neither physiography nor region explains why Nebraska has higher soil carbon levels. Rather, Nebraska is home to grasslands that store more carbon, especially in the top 12 inches of soil. Below that first foot, Dr. Franzluebbers explained, “soil carbon concentration is affected mainly by pedogenesis and not by contemporary management.”

Pedogenesis and Land Management

Pedogenesis, the process of soil formation, is affected by weathering, leaching, calcification, and other naturally-occurring phenomena. In other words, it’s not a function of human decisions about grazing practices or whether to grow trees, crops, or grasses. However, no-till farming can increase soil carbon in the top 12 inches of soil, as Dr. Franzluebber’s research in North Carolina has demonstrated.

Yet the fact remains, as the USDA Research Ecologist concluded, that “compared with cropland, grasslands are storing greater quantities of carbon”.

Additional Reading