Stocking methods refer to how cattle are managed on grazing land. Farmers and ranchers use various methods, but continuous stocking and rotational grazing are two alternatives. With continuous stocking, livestock graze one pasture for an extended period. With rotational grazing, pasture is divided into paddocks and cattle are rotated between them.

Rotational grazing gives grass time to recover, but does this stocking method result in more soil carbon? If so, at what depths? And if there are differences in soil carbon based on variables such as location, what’s the relationship between stocking methods and soil carbon levels in the Southern Plains, a semi-arid region that extends from southern Kansas across Oklahoma and into Texas?

In the eleventh and final webinar in the Grazing Land Management and Soil Carbon series, Dr. Alan Franzluebbers considered these and other questions. Dr. Franzluebbers, a research ecologist with the USDA Agricultural Research Service, provided previous lectures that examined soil carbon levels in North Carolina and Kentucky, respectively.

In the Southern Plains, Dr. Franzluebbers studied a test site that was established in 2009 and covers 850 acres. It’s located in central Oklahoma and has wet winters and dry summers. The soil drains quickly but supports tallgrass. That’s important to note because for many years, grasslands like this were converted to croplands before returning to their native, grassy state.

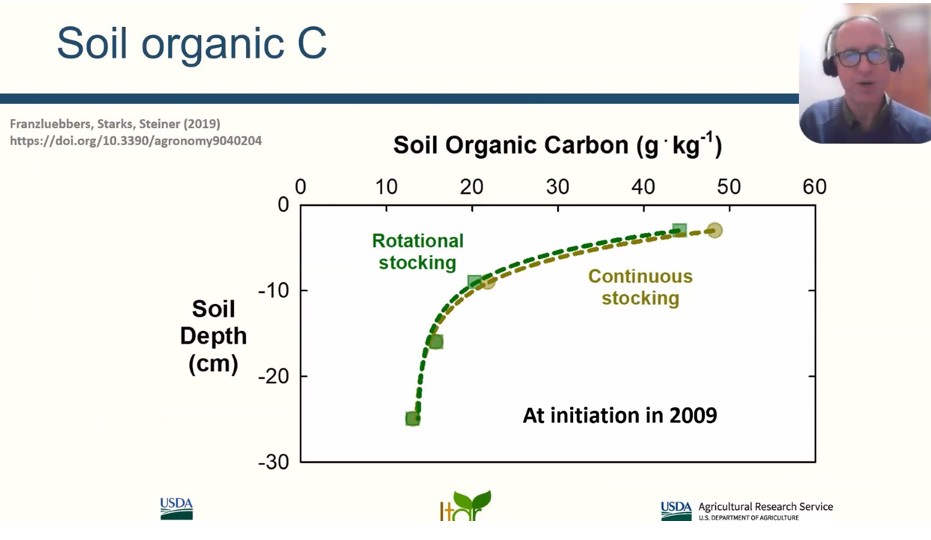

Dr. Franzluebbers thesis was that rotational stocking would lead to greater amounts of soil organic carbon due to what he called the “greater residual forage mass, surface residue cover, and deeper and more vigorous rooting” of grasses. He performed soil analysis at various depths over a three-year period and observed that soil organic carbon was highest near the surface and declining with depth. That much was expected.

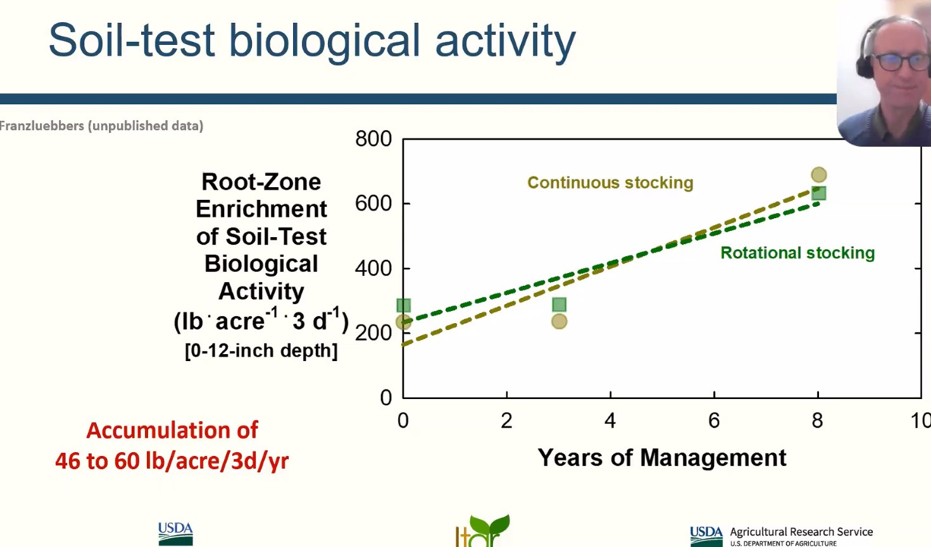

What data from 2009 revealed, however, was that there was no significant difference in soil organic carbon between pastures that were rotationally grazed and pastures that were continuously stocked. Over time, however, both stocking methods resulted in higher levels of soil biological activity, which helps support healthy and more resilient soil.

Although the study’s results did not prove Dr. Franzluebbers’ original thesis, they did support the rationale for his study. As he said about grasslands, “Since the turn of the millennium, greater recognition of their role in conserving soil, promoting biodiversity, stabilizing farming communities, and providing numerous ecosystem services has led to renewed interest in grassland functions”.

It was a fitting conclusion to an excellent 11-part webinar series – and a reminder that grasslands and the cattle who graze them don’t just help sequester carbon. They also promote soil health.