Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), or bird flu, isn’t limited to chickens, ducks, geese, and other domesticated or wild birds. It can also spread to cows, a different animal species. Dairy cows that are infected with HPAI generally recover, but they experience fever, lethargy, loss of appetite, changes in manure consistency, and a decline in milk production.

Initially, scientists were surprised by the “spillover” of HPAI from birds to dairy cows; however, viruses can “jump” from one species to another. In addition, scientists were concerned about finding the bird flu virus in raw milk: milk that has not been pasteurized. During pasteurization, milk is heated to kill viruses and other potentially harmful microorganisms.

Transmission and Infection

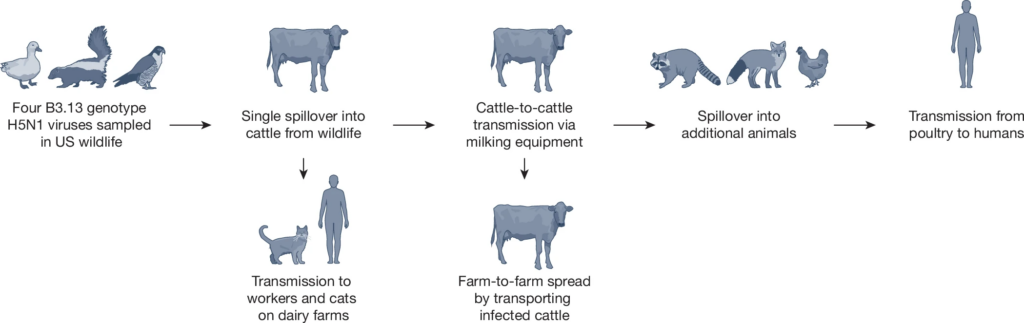

The first bird flu cases in cows were probably caused by contact with infected wild birds. These birds fly over farms and pastures during seasonal migrations or during daily flights in search of food and water. Because the HPAI virus is present in excrement, bird droppings can contaminate a dairy cow’s environment. Feed, water, and milking equipment all become potential sources of transmission.

Once the bird flu virus enters a single cow, it can spread to others. Large herds that live closely together are especially susceptible. Most dairy cows recover from the virus, typically in a matter of days and weeks. According to the USDA, there is no evidence that the virus actively replicates within the body of a cow other than its udders, which contain the mammary glands that produce milk.

Treatment and Management

There are no available vaccines or therapies for bird flu in dairy cattle. Instead, treatment focuses on managing symptoms and preventing complications. For example, infected cows may receive fluids, electrolytes, and anti-inflammatories. Infected cows are usually isolated from the rest of the herd, and the movement of animals, milk, and farm workers may be restricted to prevent HPAI’s spread.

Milk from infected cows is not allowed to enter the commercial food supply, and state and federal agencies like the USDA perform monitoring and containment. Generally, herds of infected cows are not killed through culling, a euphemism for selective slaughter. That’s not the case with chickens. In the last quarter of 2024 alone, more than 20 million egg-laying hens were culled in the U.S.