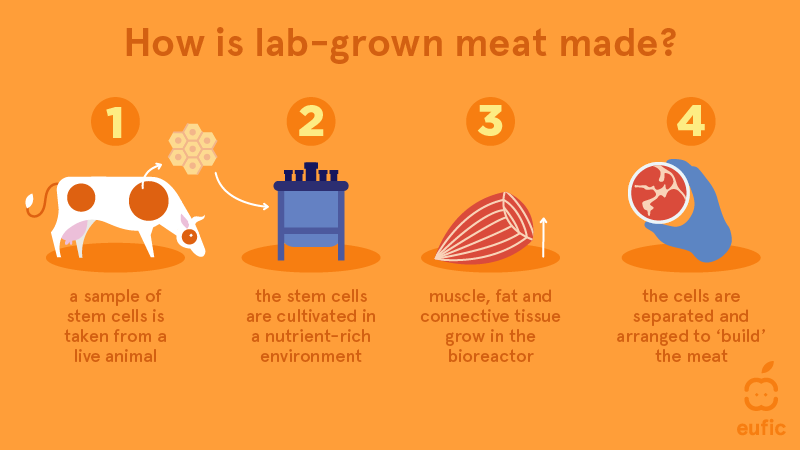

The production of lab grown meat, or synthetic alternative protein (SAP), is a complex, multi-step process. Embryotic cells are extracted and then cultured in a medium that contains fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells are then grown in a bioreactor, a piece of laboratory equipment. After several weeks, the SAP is removed and then formed into a final product. The diagram below provides a simplified version of this process.

Bioreactors vary in size, but they include a pump, stainless steel tank, thermal jacketing, aerator, and piping. Heat and pressure are applied to the tank to promote cellular growth and differentiation. Eventually, the soup-like mixture inside becomes a solid. Cellular scaffolding determines whether this solid is shaped like sheets or chunks.

Scaffolding and Tissue Engineering

Scaffolding provides structural support and points of attachment for the embryonic cells that would otherwise move or float within the bioreactor. These scaffolds aren’t like the metal and wooden structures used in building and construction projects, however. Rather, they’re made of biomaterials, substances derived from plants and animals. Typically, the SAP industry uses plant proteins; however, food-safe gelatin proteins may be used in the future.

The concept of cellular scaffolding isn’t particular to the SAP industry. As the video below shows, scaffolding can also be used to regrow human tissue.

In the SAP industry, the cellular scaffolding that’s used resembles steel wool, writes Chloe Sorvino, author of the book Raw Deal. Instead of metal wires, however, this tightly bundled structure is usually made of soy proteins. That’s important since some SAP proponents claim that lab-grown meat is the same as traditional meat but without the animal. It also shows how SAP differs from plant-based meat, which is made exclusively of vegetables or legumes.

Chunks and Sheets of Meat

At the SAP producer Upside, which makes the first FDA-approved lab-grown chicken, scaffolding enables muscle cells and connective tissue cells to grow together in large sheets. Sheets of poultry cells are removed from bioreactors and then formed into sausages and cutlets. SAP can also be grown in chunks, or aggregates, that are later formed into patties. Regardless, it’s important to understand that SAP producers do not simply open a bioreactor tank and remove chicken nuggets, hamburger patties, or a steak.

Stacked and Combined

SAP sheets are stacked together in a process that was adopted from a method used to grow tissue for human transplants. Each sheet is about the thickness of a sheet of printer paper. The sheets naturally bond to one another before the cells die, and the layers can be stacked into a solid piece of any thickness. These thin film-like sections of meat can be designed to replicate the content and marbling of real meat, and SAP providers can fine-tune the recipe based on consumer preferences. With SAP chunks, aggregates can be put into a Petri dish, which conveniently has the shape of a hamburger patty.

In our next article, we’ll examine the energy consumption that the SAP industry requires.