Dr. Mark Liebig is a soil scientist at the USDA’s Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory in Mandan, North Dakota. Recently, he presented the tenth webinar in an 11-part series called Grazing Land Management and Soil Carbon. The topic of his talk was “Soil Carbon Responses to Grazing Land Management in the Northern Plains,” a semi-arid region characterized by mixed-grass prairies.

North Dakota and the Northern Plains

The Northern Plains are part of the Great Plains, a broader geographic region that stretches from Canada to Texas. Winters in the Northern Plains are cold, but the climate is changing. Since 1900, North Dakota has warmed more quickly than any other state in the U.S. Extreme weather events with heavy precipitation have increased, but so has overall aridity.

Compared to other parts of the Great Plains, the Northern Plains have higher levels of soil organic carbon (SOC). In North Dakota, about 50% of SOC is in the top 0.3 m of soil. Grasslands have higher SOC levels than croplands, but surface-level SOC can be lost easily and is difficult to reclaim. “The most important thing,” Dr. Liebig said, “is to keep grasslands as grasslands”.

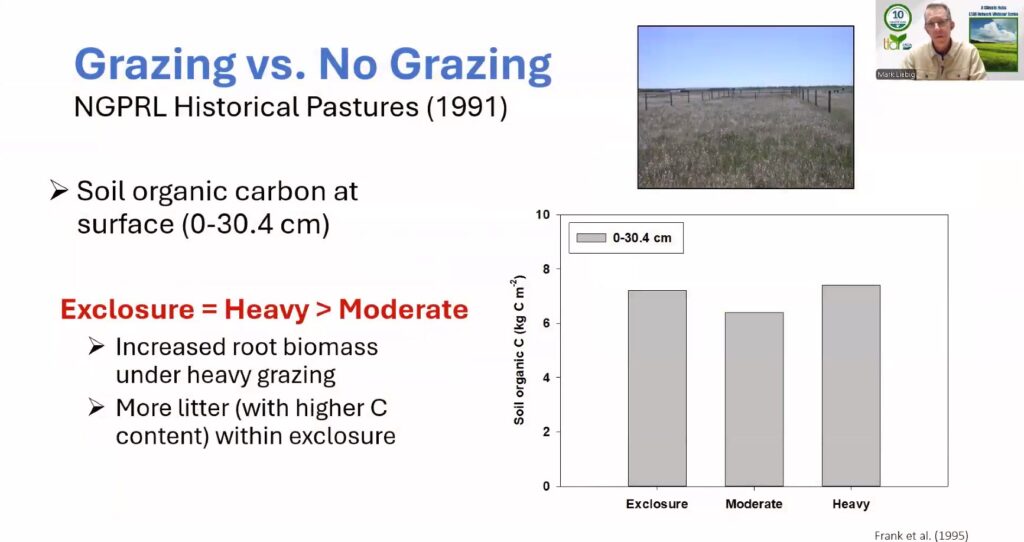

Grazing Levels and Root Biomass

Because the Northern Great Plains Research Laboratory was founded in 1916, soil scientists have years of research at their disposal. When soil samples were taken in 1991 and 2003, heavily grazed areas had higher levels of SOC than exclosures or moderately grazed areas. Dr. Liebig attributes some of this difference to the greater root biomass in blue gamma grasslands that are heavily grazed.

There are other factors to consider as well. At surface depths, heavier stocking rates are associated with greater SOC levels. The spread of cool-season grasses and woody species have also increased soil organic carbon. In addition, SOC levels are higher when grasses are interseeded with Anik. This grazing-type alfalfa has a greater lateral root biomass than hay-type alfalfa.

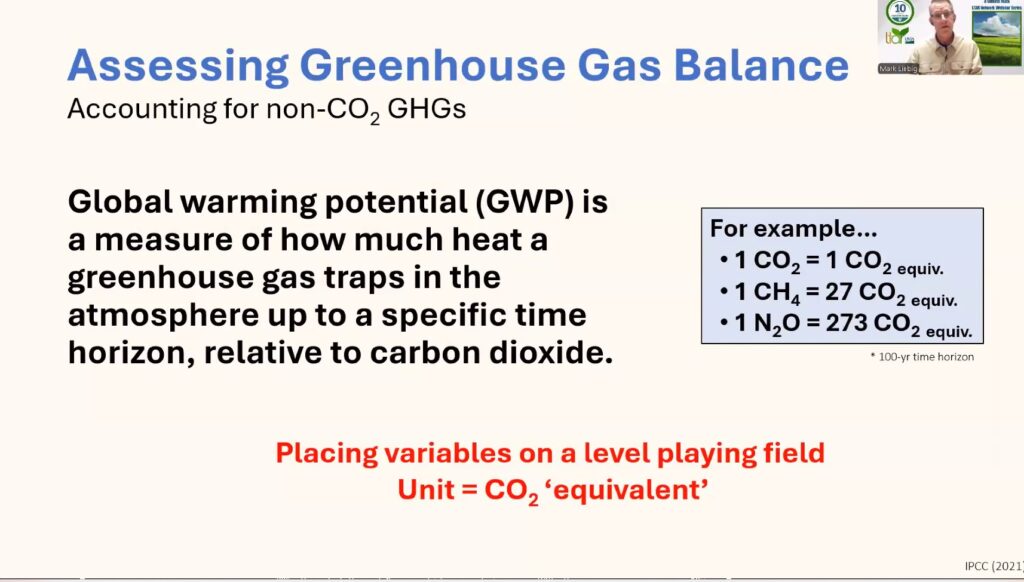

Global Warming Potential in the Northern Plains

Dr. Liebig concluded his presentation with a discussion of global warming potential. One unit of methane (CH4), a greenhouse gas that cows produce through digestion, is equivalent to 27 units of carbon dioxide (CO2). One unit of nitrous oxide (N2O), a greenhouse gas that comes from applying nitrogen fertilizers and manure to farmland, is equivalent to 273 units of CO2.

“If we want to talk about climate mitigation,” Dr. Liebig said, “we need to talk about all three gases”. He added that because the Northern Plains is a semi-arid region, “our soils are methane sinks because they are dry for most of the year.” That’s good news for carbon sequestration, but the fact remains that SOC is easy to lose when grasslands don’t remain grasslands.