This article was submitted by Steve Melito, a farmer, writer, and member of Go Natural Education.

New England winters are cold, long, and dark. You might say it takes a tough old bird to live here. At Cole Mountain Farm in Adams, Massachusetts, we’re raising a small flock of chickens, including some younger birds that are making it through their first winter. It’s been cold enough for eggs to crack, and there have been plenty of days when “the girls” don’t want to come out of their coop.

Chicken coop heaters help, of course, and the panel-style heaters that we use seem safer than heat lamps. We also have heater plates so that the chickens’ water won’t freeze. A trip to our local Tractor Supply is always welcome, and it’s where we buy organic feed and pine shavings for bedding. Yet winter chicken coop care that’s sustainable doesn’t always involve a purchase.

In addition to thrift, it takes observation, research, and experimentation. In short, there’s some science behind it.

Heat Loss and Thermal Insulation

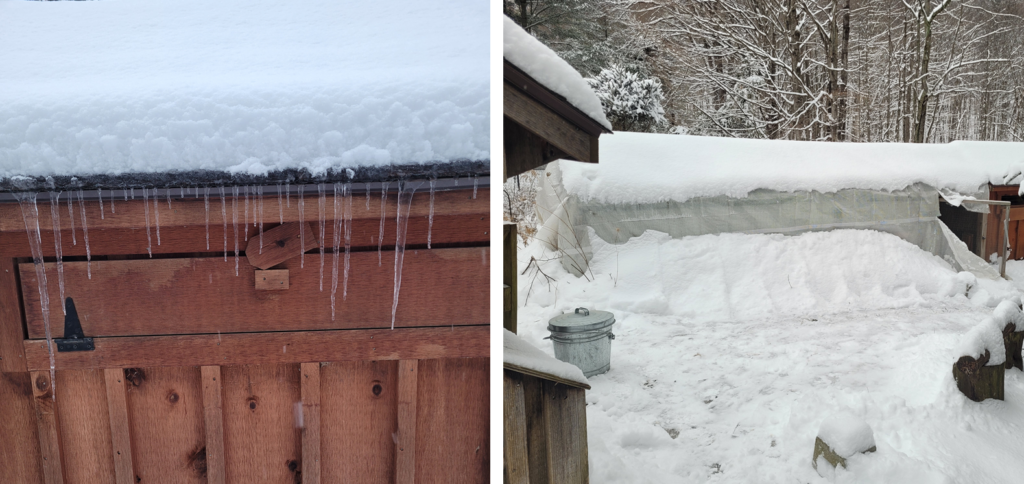

As you can see from the picture on the left above, there are some icicles along the roofline of the coop. That’s a sign of heat loss, but it’s also a signal that the air inside the coop might be warm enough to melt snow on the roof as it escapes. Chicken coops are drafty but buttoning them up tightly can make it hard for moisture and odors to escape. That’s not healthy for chickens.

Most of the icicles are small, so there probably isn’t excessive heat loss from our coop. Some icicles probably formed on our last sunny day, which was followed by a night cold enough to freeze any meltwater. The thick layer of snow on the roof is a plus because it’s a natural insulator. That’s because snow contains a high percentage of trapped air, which limits heat transfers from the warmer coop to the colder outside air.

Above, the picture on the right shows our chicken run. The grayish plastic between the snow is a solar cover that was meant for a greenhouse. This is the second winter it’s been on the coop, and it’s more insulating and durable than regular plastic sheeting. It also has metal grommets for fastening. The snow on the run’s roof also provides insulation, and we’ve piled snow along the sides for good measure.

The Deep Litter Method

Chicken manure is a nutrient-rich fertilizer, but it needs to be composted first because raw manure can burn plants with its high nitrogen and ammonia levels. By using the deep litter method, however, it’s possible to compost manure and carbon-rich bedding right inside the coop all winter long. Spring planting is a long way off, but we’ll be ready when it arrives.

Among its advantages, the deep litter method builds a microbial ecosystem that generates heat in winter and helps controls ammonia from the chicken manure. This coop management technique is not maintenance-free, however. Along with a proper balance of manure and bedding, compost needs air for decomposition.

As the picture on the left shows, maintenance involves turning the bedding that’s inside the boxes where the chickens sleep at night and lay their eggs by day. Farmers tend to repurpose what’s not broken, and we use an old wooden ruler with a jagged edge that some folks would have thrown away. Every few days, the manure/bedding mix in the coop gets turned over.

The “deep” in the deep litter method is essential. If you look at the picture on the right, you’ll see a light-colored rectangular board where the handle of a shovel is resting. That board helps keep the litter from falling out the back door of the coop when it’s opened. Since it’s 15 inches tall, it also provides a visual cue about the depth of the litter. Generally, 12 to 14 inches is ideal.

Charcoal in the Chicken Coop

You don’t have to be farmer to know that chicken coops aren’t sweet-smelling. Yet there’s a market for what amounts to chicken coop potpourri. On the right is the back of a package that contains some nifty natural ingredients, mainly the leaves and petals of flowers. Yankee farmers are thrifty, however, and in winter the charcoal from our fireplace is plentiful. (Flowers this time of year are rare.)

Why use charcoal in a chicken coop? It manages odor by reducing ammonia fumes. This porous material binds with manure and absorbs moisture and gases that can irritate chickens’ eyes and lungs. Charcoal also improves the quality of the fertilizer that the coop is creating, and it’s safe for chickens to eat in small amounts. Since fine, powdery charcoal can cause respiratory issues, there’s no need to crush up the bigger chunks.

Clean Coop, Sheltered Run, Happy Chickens

After turning the litter and adding some charcoal, it’s time to add some fresh pine shavings to the floor of the coop and to the nesting boxes. Chickens are notoriously nosy, and the one in the picture on the left came to investigate. Also, while working in the coop, it’s wise to open the panels and let some fresh air blow through. Maybe winter winds aren’t so bad after all.

As the picture on the right shows, some of the “girls” would rather spend the day in their run than out in the snow. They can go outside whenever they want, but they seem happy enough to eat and scratch. During the dead of winter, we add some homemade chile powder to their feed. Last summer’s crop of datil peppers is this winter’s supplement. These orange-colored chile peppers as much as 100 times hotter than jalapeños!

Capsaicin, the active compound in chile peppers, acts as a natural antimicrobial to reduce gut pathogens. It also improves digestive enzyme activity, boosts overall immune function, and deters rodents in search of winter forage. Because chickens lack the pain receptors that respond to capsaicin, they can eat it freely. That’s more than most of us can do, no matter how cold it gets in New England.