When a cow chews, or masticates, grass or other types of roughage, saliva is secreted from glands in the animal’s mouth. This clear liquid helps to soften the cud, as it’s known, and aids in digestion. Yet, there’s a lot more happening in a cow’s mouth than meets the eye. There’s a reason that cows chew their cud for a while, and it’s not because they don’t have many teeth.

Did you know that cows don’t have top front teeth? That’s because they have a thick dental pad there instead. Cows use this dental pad, along with their bottom teeth, to grab grass, twist it, and pull it. A cow’s rough tongue helps with this process. Other animals need front incisor teeth for cutting, but that’s not the case with cows. Instead, they eat and swallow their food quickly, without chewing it right away.

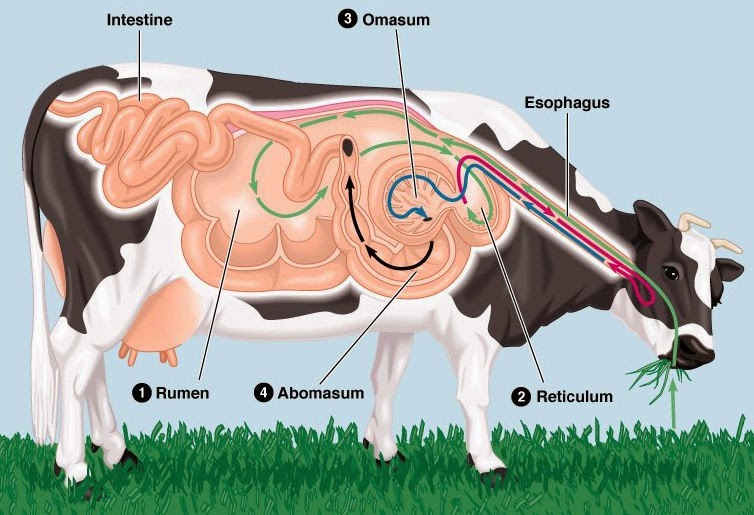

Unlike humans, cows have four stomachs. The largest of the cow’s stomachs, the rumen, is where food travels after the cow swallows. The other three stomachs – the reticulum, the omasum, and the abomasum – also have roles to play. A cow’s stomachs all work together in a closed recycling loop, and in conjunction with the animal’s salivary glands.

As we’ve learned previously, the grass that a cow eats passes from its mouth through the esophagus to the rumen, a drum-like stomach that contains millions of microorganisms. Some of this chewed grass is conjugated into balls that float in a digestive medium. This watery substance contains microorganisms that help digest the grass and also have an acid stomach producing interaction. The rest of the grass passes through the cow’s digestive tract instead. The acidity level in the rumen is important for digestion, so keep that in mind as you keep reading.

Within the rumen, some grassy balls float and others sink to the bottom. From there, the “sinkers” pass to the reticulum. This small stomach is mostly muscular, so the reticulum grabs these grassy balls and irritates them, forcing them back up to the cow’s mouth. With the aid of more saliva, the cow then masticates, or chews, this partially-digested material before swallowing it. In turn, this material passes back through the esophagus and into the rumen, where more of it is digested.

From the rumen, some of the grassy material passes into the omasum, the cow’s third stomach. The omasum is like a big dehydrator, but it has a massive amount of water flowing into it. The omasum separates the water from the digestive material and recycles the water back to the salivary glands. This fluid is mixed with bicarbonate, an ingredient in bovine saliva, to produce a natural antacid, or buffer. This is important because the pH, or acidity level, in the rumen needs to support digestion. Too little acid would be a problem, but too much acid isn’t good for the cow either – just as in humans with heartburn. So, instead of taking an old-fashioned antacid like baking soda (sodium bicarbonate) and water, the cow salivates.

Then the dehydrated digestive material passes to the abomasum, which is like the human stomach. The abomasum contains hydrochloric acid, enzymes and peptides for digestion.

When a cow chews its cud then, it’s supporting a digestive process that begins with mastication and salivation, involves multiple stomachs, and requires the proper pH, or acidity, level. The entire digestive process takes a while, as you may have noticed if you’ve spent a day on a farm or ranch. In the morning, cows typically graze until it gets hot. Then in the afternoon, they sit and sleep or chew their cud. If it’s cool enough in the evening, the process begins again.

The end product of this whole magical recycling process is cow manure, which has its own valuable natural qualities. We’ll discuss this in a future article.